And his disciples asked him, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?”

John 9:1, ESV

One of the most useful - and most difficult - concepts we can study is how things move or change together. This kind of study is the crux of a lot of work in economics, but it also applies more generally to life.

When something happens to A, what happens to B? When two things share a relationship, we can study that relationship and see what wisdom can be found.

This kind of analysis can easily fall apart, however, when we start to read too much into a given relationship. It's one thing to say a relationship exists, but it's another thing entirely to make claims about what causes the relationship to exist.

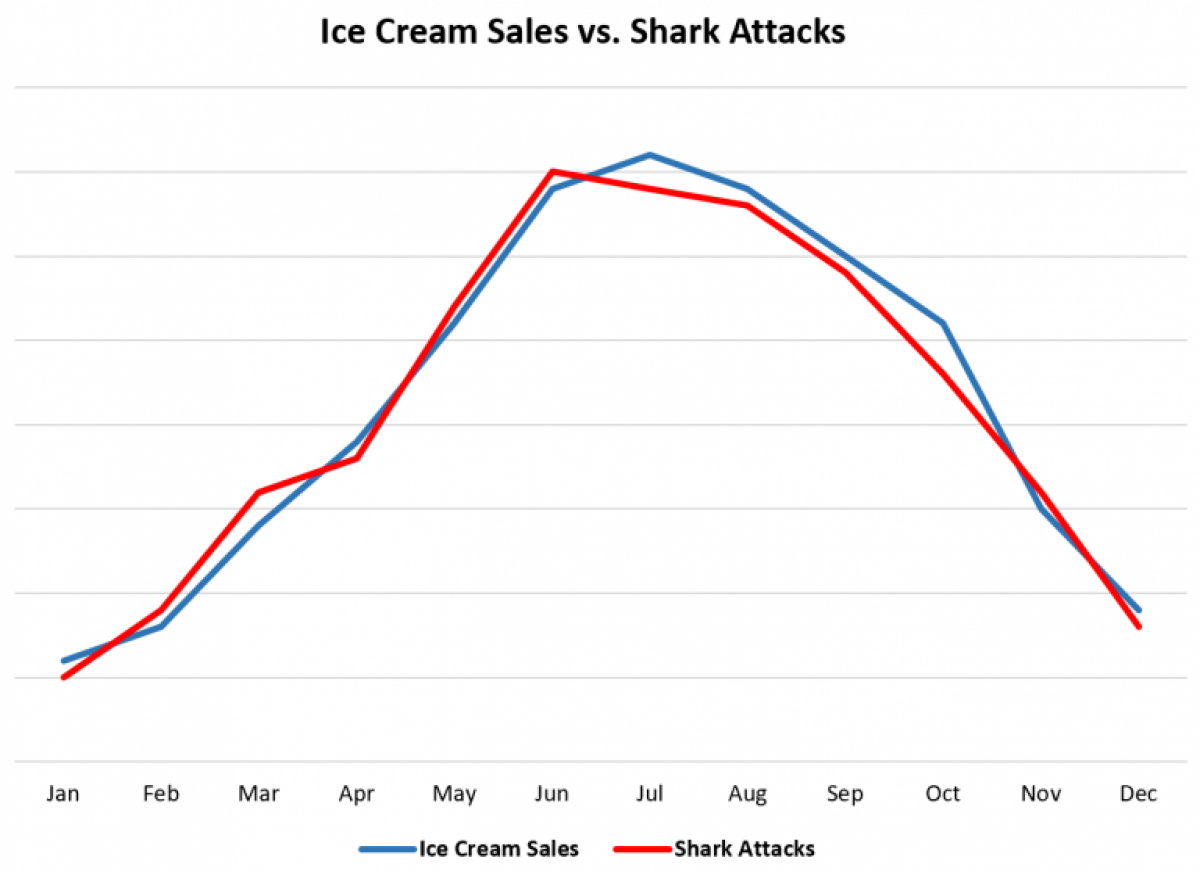

Consider this example:

The graph above shows monthly ice cream sales compared to monthly shark attacks around the United States each year. It sure looks like when ice cream sales go up, so do shark attacks. But does one cause the other? Are people getting attacked by sharks because sharks love ice cream? Or is it that after being attacked by a shark, ice cream sounds particularly appetizing, thus causing ice cream sales to rise? It's probably not any of these scenarios. Shark attacks and ice cream sales seem to share a relationship, but it's a stretch to say one causes the other.

This is something we have to internalize. We are very quick to attribute an outcome to a cause. It's part of how we make sense of the world. Sometimes causes are obvious, but sometimes they are not. Here are three rules for thinking about cause and effect relationships:

1. Correlation does not equal causation. Just because two things move together (that's what correlation means) does't necessarily mean one causes the other. This is a common saying in statistics.

2. Even when one thing causes another, the direction can be hard to discern. So we've figured out that A and B have a relationship, and it seems that one is causing the other. Before you jump to the conclusion that A definitely causes B, have you considered that B might cause A? What if there is a third variable C which causes A and B to move together?

As economist Thomas Sowell writes, "Even when there is in fact a causal relationship between two things, that by itself does not tell us the direction of the causation...."1

3. Relationships can change over time. Just because two things have a relationship now doesn't mean they will always be related the same way. Correlations change over time.

This idea has significant implications for Christians. Just like all humans, we are quick to think in terms of cause and effect. When we apply this to life as a believer, it leads us to think we know how God should do things. We may inadvertently come to see God as predictable.

We have to allow the Holy Spirit to challenge the way we make sense of the world.

In John chapter nine, Jesus is passing along the way when he sees a man who was blind from birth. His disciples ask him this question: Who sinned that this man was born blind. Was it his parent's sin, or his own sin? The questions assumes a cause and effect relationship.

The disciples seem to believe they know why he was blind. The man is blind because someone sinned. Their question presumes that the relationship between sin and the man's blindness is so obvious it can be taken for granted.

Jesus corrects them. The man was not born blind because of sin, but because God had something larger happening. "It was not that this man sinned, or his parents, but that the works of God might be displayed in him."(John 9:3, ESV)

We naturally try to make sense of the world, and that in and of itself is not bad. We simply have to be open to the idea that the way we see things may not actually reflect the way things are, especially when it comes to how God works in, through, and around us.

1. Thomas Sowell, Wealth, Poverty, and Politics; pgs 382-383

Found in:

Uncertainty